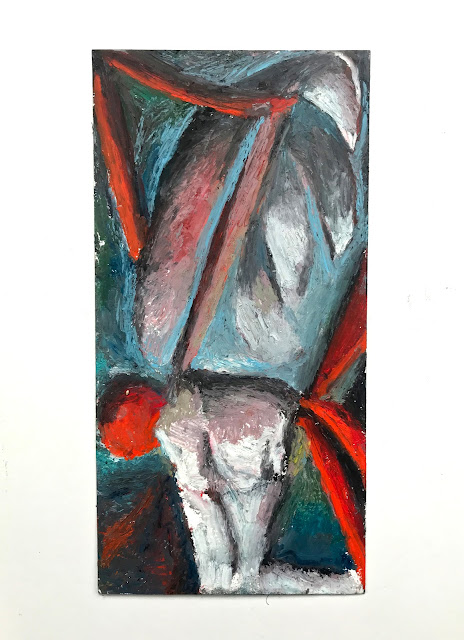

Conditions To Rectify Lost Time/ oil on canvas/ 180 x 160cm/ 2019

courtesy of the artist

SOTP: Hi David, thanks for coming along to do number three in this new series of interviews. Well, of course we don’t know each other from Adam! But I like how in the painting community there is a very often this sense of common purpose and sharing of ideas, and I was prompted to contact you initially because I had come across your excellent ‘To The Studio’ podcast interviews. In fact it seems to me that for all its distractions, the internet is providing us with a real life-line of interesting art things in these difficult Covid-19 times. However, 'To The Studio' predates the lockdown- so can you tell us about how it all started, and how you have managed to keep it going through the lockdown?

DA: No problem- it's a pleasure, thank you for asking me to come on. Funnily enough, ‘To The Studio’ started out from feelings similar to those you've mentioned, in relation to common purpose and sharing of ideas and experiences. The reasons for starting the podcast were tenfold.

After I left art college a few years ago I was having a tough time emotionally, and feeling isolated and confused living in a small village in Kent. I'm sure it's an experience shared by a lot of art students daily just now! I deeply missed feeling a part of something, having everyday interactions and conversations with so many artists and thinkers that I admired, which in turn can lead to many breakthroughs and opportunities via that network, both individually and as a group. I thought it was possible that I wasn't the only one feeling those negative things, and that maybe something as simple as a conversation could help to break down those imaginary walls that can seem to build up around one as a creative, and in their place forge positivity and communities of support through generosity of honest conversations and a sharing of them.

I also wanted to get better at talking about art, and to continue doing something I've always loved doing- learning about how other artists operate and also their own experiences. This was coupled with my acute awareness of the broad, rich and brilliant undercurrent of artists, musicians, curators etc., that make incredible work and that we don't hear or see enough of. I felt that somehow all of that needed to be acknowledged and celebrated much more than it is, and most importantly, that they deserved to be heard and shared.

So I've given you a long answer here, but all that was stirring around in my head, and as a lover of artists’ interviews anyway I thought a podcast seemed to tick all the boxes- despite my fears of being recorded! My hope was that the podcast might have the potential to help generate a community of artists and thinkers, not just in London but in a wider sphere too. And if I were to make myself vulnerable that might be something other people could relate to as well, so I gave it a go! I should also mention that one of the most important elements was that the podcasts are free and accessible to everyone, anywhere, at any time.

In terms of continuing through lockdown, my audio wizard producer Theo Byrd suggested a few ways I could record remotely without equipment and it didn't take us long to set it up and get going...

SOTP: One of the things I really like about your podcasts is that they can be very revealing about painters’ experiences of art education. Very rich and rewarding for most it seems, but sometimes throwing interesting light on what we might call the ‘struggles’ of the painting student to find a place within the contemporary art scene. We can all relate to that- it doesn’t really change much after art college either! So next question is, what were your own experiences of being a painting student- what drew you to that area of Fine Art, and was it easy to stick to your own paths of investigation during undergraduate and postgraduate study?

DA: Firstly I would like to start by saying that I feel like I am in a very privileged position to be able to call my art practice a struggle, and that I'm grateful for that!

I had a very sheltered art education throughout school, nobody in my family was involved in the arts or had any invested interest in it, and I was the first of my family to go to university. I didn’t begin to make paintings until I found myself on the Fine Art Pathway on my Foundation course about 10 years ago - and haven’t looked back since (well, maybe I have once or twice).

For me my undergraduate was essentially a three year search- exploring who you might be as an artist, and mapping your path out of what you find. Hopefully at the end of that process you are at the point where you have built the architecture of a practice that you believe in, which allows you to walk down your path and out into the world with purpose. Whereas for my postgraduate I felt it was more of an excavation - I desperately wanted to break down all of those previously known conventions of making and thinking, rearrange the pieces, take some away, add some new ones, with a heightened level of critical rigour and hopefully have something interesting at the end of it all.

In that sense, sticking to my own path was fairly easy on my BA as that path wasn't built yet- I was experiencing everything for the first time and the enjoyment I found in exploring the new was incredibly exciting. My MA was a different matter, and a lot more difficult for many reasons, but possibly the main things that I learned can still threaten to steer me away from my own path, in comparing myself to others, taking on too many of others' opinions, and worrying about what happens outside of my practice. This is all part of one’s learning experience, but in the pace and intensity of the Royal College those traits seemed to adhere themselves to me, and left me flailing a fair few times, and still do on occasion.

Elysian/ oil pastel on watercolour paper/ 2020

courtesy of the artist

SOTP: To look at your own practice in more detail now, which as I’ve said I’m only getting to know a bit about recently- there are so many interesting things going on. Coming to it fresh and uninformed, the first thing that strikes me about your recent work is that it is very idiosyncratic. I like that in painting, when it doesn’t look like anything else that’s around just now.

However I see strong precedents (correct me if I’m wrong!) in Surrealism- I’m thinking of Miro here- also, something of Guston going on, and the more that I’ve looked at your work, also something of 1980's painting (here I do not mean to be derogatory!) I bring it up simply because I think so much painting of that era had no real or interesting relation to space- it often took painting into a flattened out and illustrative space (for instance Schnabel, or Clemente, or even Polke). However in your paintings there is much more engagement with, and feeling of, space- I’d draw a spacial comparison with, say, Terry Winters’ or Basil Beattie’s work and yours- paintings that you can wander into and around.

Anything here that chimes with you, or that you disagree with?

DA: No need to apologise! Similarities are impossible to escape, and I'm learning to become more accepting of them- it makes it a little easier when names like Terry Winters pop up! You've drawn many comparisons, so I will try to unpack some of my interests in painting which might in turn address the insights you've made…

The spatial element of painting is an interesting place to start, it's something in painting I have thought about a lot over the last few years, and wrote most of my dissertation on. In many ways the notion of ‘wandering around in space’ is a feeling I often feel within my daily reality. Paintings seem to have the greatest hold over me when they are anchored in a physical realm yet simultaneously take me out of my context, and speak intimately to me through carrying promises in their mystery, of ‘somewhere’ or ‘something other’. One of the ways painting can do this to me is through their gaps, space, breaks etc.- a kind of foothold, but also with an absence pregnant with promise.

We have become so used to instant rapid information, dissolved down into easily digestible, short sound bites, that the fertile ground of questioning the unknown and allowing it into our experience can be cast aside, forgotten, and at worst classified as an indulgence. Maybe painting for me is a reaction to all that, and where the element of space comes into play.

At the moment the work I make is a yearning for, and an inquiry and exploration of, an unknown space. A search through, and out of, my known physical realm into another of continual open-ended mystery. This is a choice as a painter, a commitment to openness and a belief in the immense life giving potential that lies within all manner of that uncertainty. Armed with faith that if we are to take painting as an ontological medium, painting can be used as a vehicle to open up information in our environments and bring us closer to potential truths or meanings.

Attempting to demystify images I make seems futile, and undermines the generosity in their vulnerability (as well as highlighting the limits of our language). Often I attempt to explain content in painting and it fades away, disappearing out of my grasp, much like when you try to recount a dream. The images, sounds and sensations that were so vivid, once recounted, fade into nothing, and their once profound imprint on your psyche vanishes.

Although the work may contain echoes of the recognisable, at present specific objects or forms are never placed within the image. This is not a judgement on others' work by any means, but is currently intrinsic to my sensibility, and the use of specific objects and forms would risk the work vanishing purely into recognition, and any potency found in its questioning ends. To champion paintings' abilities to exist on the potent brink of potential between what we know, and what we don't, is perhaps where meaning for me lies. I’m learning to allow myself to be comfortable with images I cannot fully comprehend, to indulge in their oddities, impossibilities and nonsenses…and embrace them. Images that are not given to me to fully understand, are far more closely linked to my everyday reality than something fully recognisable, formulated and solid and I am thankful that is the case.

SOTP: So how do you go about making your paintings? Do you have any special approaches to preparing your canvases, or the sorts of paints you use? And what are the lead-ins subject-wise, in the collecting of visual material you work with?

DA: Paintings can begin in an all manner of ways, often they begin out of a quality I have found in a drawing that excites me, with others I am filled with a need to make a mark and the painting intuitively begins from there. Others begin from a momentary vision I may have (which has been happening a lot more frequently recently).

I use drawing and painting to facilitate an instinctive investigation into making sense of what it is to be in this world. To be here on the Earth right now. Mapping my experience of the everyday primarily through drawing, I use both exterior stimuli and interior dialogues as influences. The drawings begin to open up into painting when there is something within them which, at one and the same time, is both mystifying to me, but also simultaneously holds a tangible energy which relates to lived experience.

Using this brink of potential as a starting point, the act of painting then works to unpack, deepen and enrich this quality found in the original drawings or experiences.

In terms of how I prepare my canvases, I wouldn't say I have any special techniques or methods. I don't spend too long preparing their surfaces as the paintings are built up/ down quite substantially over time and the surface undergoes rapid transformation. Usually a few coats of primer will do and I am away. As for paints, I use fairly high volumes of the stuff so unfortunately I am not in a position to be too picky. Apart from a few select Michael Harding’s here and there, most are purely based on what I can afford at the time.

SOTP: Could we talk here about two paintings in particular, one is very small and the other is gigantic! I’m thinking of ‘Distant Encounter’ (quite small) and ‘Offerings to the Ultravista’ (coming in at an immense 7 metres wide), both from 2018. Yet they both speak to the space thing you and I have been talking about. Also, I think there is a bit of a Gustonesque playfulness going on in the small piece, and the very large work in its dimensions has an immediate relationship to Picasso’s Guernica (albeit again with more spatial depth in yours). Can you tell us how you have moved around in your paintings scale-wise, what challenges this presents, and also the specifics about these two pieces? And what sort of studio set-up do you have? Are there any particular restrictions you are dealing with under lockdown?

DA: Both of these paintings you mention were made whilst I was studying at the Royal College two years ago, when I had the luxury of a much larger studio than I have now. I tend to be working on a lot of paintings at the same time of varying sizes, anything from 5-20 paintings simultaneously - I am frequently restless in the studio and my time in there is often intensive. I often have a physical need to be continually doing, and if I only have a few paintings on the go I am very guilty of over-egging it. Working on a lot at the same time removes the possibility of that happening (most of the time) and works against these instincts. I find this way of working allows the paintings to be made in spite of me, and the time involved in their gestations always throws up new possibilities and readings. ‘Distant Encounter’ was a painting that slowly grew out of that process.

In truth the opportunity to paint ‘Offerings to the Ultravista’ happened out of several chance happenings, from being gifted that set of stretcher bars, to my studio mate leaving for Christmas vacation for 2 weeks. I had become bored and constricted by previous notions of making, and began to think about the size and shape of canvas as restrictions that could be made flexible, in order to open up new possible ways of working. I also wanted to take what could be the only opportunity I might ever have to make a painting that size, and I tend to relish in challenges like that - throwing myself into them without a plan, involving intense periods of making…Will it work? Will I fall flat on my face? It makes me feel alive. I can't say if either happened, but I learned a hell of a lot in that period of making, and I hope I get the opportunity again with the experience I am armed with now.

I welcome any challenges, as within that experience of pushing myself to my known limits, lies the potential opportunity for change. Secondly, physically working on that size was a thrill, and allowed the physical joy of making it to sing through, and that element of painting has always communicated to me. I often worry about the whole ‘White, Male, British, Big Abstract Painting’ thing and if it was all alright to do? But sometimes you just have to say, ‘Fuck it, I’m gonna do it anyway’…and I’m glad I did.

In terms of my restrictions, I haven't been able to visit my studio since lockdown began. I've managed to build a workstation at home in my flat that allowed me to continue working, but recently I've only been able to work through some works on paper.

SOTP: Finally, is it possible just now for you to talk about what lies ahead? It’s such a strange time for artists- for some of us there is a sense of constant, maybe even monotonous and unlimited (if restricted) time to make work, but perhaps without the light at the end of the tunnel of when or where it’s going to get shown. How are you dealing with things and what’s in store for your next exhibition outing do you hope?

DA: I'm not sure what lies ahead, but I hope things don't go back to the ‘normal’ we are all used to, and as a community of artists we can continue to shake-up and rethink those conventions that don't really serve us. There have been many initiatives that have responded to the tough situation creatives find themselves in, including Matthew Burrows’ formidable Artist Support Pledge https://www.instagram.com/artistsupportpledge/?hl=en and Art for Covid https://www.instagram.com/art.for.covid/?hl=en exemplifying the kind of generosity that truly supports artists, makers and charities that are in serious need of help. These aren’t issues that should cease once lockdown ends.

I have personally found it quite tough to make work in lockdown. It feels quite complicated to unpick exactly why, but I think it probably has something to do with the close proximity of my work and living space - and the inability to distance the two. As I mentioned before, the process of making is always intense, and when things don't go too well there is no chance to escape it and run away for a bit. I need that processing time away from work. With that said I'm grateful that I've been forced away from making, and have been able to take the time to see the work a bit more objectively. I've been learning a lot about myself and my practice from the distance away from it, and most importantly have been allowing myself to enjoy spending time on so many other things that bring me joy, that I’ve neglected or forgotten about.

As for where the next exhibition outing will be I hope it's full of beautiful paintings, great friends and a never ending supply of ice cold beers.

SOTP: It’s a beautifully imagined scene! Let’s hope we are all out there doing that, sooner rather than later. Thanks so much for sharing your insights with us David.

David Auborn was born in Kent, England, and now lives and works in London.

He took his BA in Fine Art/ Painting at Brighton University between 2009 and 2013, and his MA Fine Art/ Painting at the Royal College of Art in London from 2016 to 2018.

His recent solo exhibitions have been 'The Thing That Moves' (2019) and 'Distant Matter' (2017), both at Pierre Pournet, Bordeaux, France.

Recent group exhibitions have included 'A Hand Stuffed Mattress' (2019) at Terrace Gallery, London and 'Nouvelles Acquisitions' (2019) at Maison Frugès - Le Corbusier, Pessac, France.

He is also the founder and editor of 'To The Studio' podcast interviews.